Derek Pringle, the former England cricket all-rounder, has long been hooked on the sound of music – and the collecting of it too.

Music, along with certain smells, transports me to a previous time and place quicker and more faithfully than anything else. Dr Who may have his Tardis but records, their mysteries and pleasures hidden within a tiny, circular groove half a mile long, can place body and mind elsewhere even in familiar surroundings.

The music I seek must be on vinyl records, either long players (LPs) that spin at 33 1/3 revolutions per minute, or seven-inch singles, which rotate at 45rpm, and they have, mostly, to be recorded in analogue (a continuous and complete measurement of a sound wave as opposed to the snapshots of digital recording). I don’t shun modern records but it is the sound reproduced from those old grooves as they rotate, with the help of a tiny diamond shard and some decent hi-fi kit, that gets me.

The majority of today’s records are recorded digitally then pressed into vinyl. As a result, few possess the sonic charms of analogue: rhythmic purity, the proper decay of a note, and the music captured in real time instead of being shuttled backwards and forwards as a series of 0s and 1s and then decoded. I buy such records sparingly.

Compression is the enemy of faithful and accurate sound reproduction and digital recordings suffer data compression, which removes some sound. MP3 files are the worst, as they are also subject to dynamic range compression, a practice that has been around a while but was previously limited to single instruments in the mix. Because MP3 files are designed to be heard on phones, iPods and computers, the music is made loud, with quiet passages boosted, a practice that increases the overall volume but removes dynamic range from the music, which then affects both nuance and emotion. Trouble is, this is done at the mastering stage so no uncompressed versions exist, not even on vinyl records.

The 78rpm shellacs, which were the first vehicle for the mass dissemination of music during the first half of the 20th century, are of less interest to me. I don’t have anything reliable to play them on. But I have a few dozen found on my travels, and I once heard an Elvis Presley 78 played on a modern deck (as opposed to one of those wind-up gramophone models with a sound horn from the 1920s and 30s) and it sounded dynamic as hell. Easy to see why bible belt America felt it was the Devil’s music when it was first unleashed in the 1950s.

But is it solely the music or the vinyl discs on which it is transcribed that has moved me to spend so much time and money seeking them out? Social psychologists such as Sam Gosling, of the University of Texas and author of the book Snoop: What Your Stuff Says About You, would say neither. According to them, everyone collects something. It is part of the human condition and hardwired from birth; things like comfort blankets, dummies and cuddly toys trigger our collecting instinct from the cradle.

Gosling, and others like Mark B McKinley, professor of psychology at Lorain College in Ohio, point to seven main reasons why most of us collect – be it records, beer mats, stamps, football programmes or porcelain cups.

Those reasons are as follows:

1) For fun (the majority of collectors)

2) For investment

3) To expand one’s social horizons

4) To preserve the past (most museums are collections)

5) For psychological security to fill a perceived void in one’s self

6) As a claim to distinction so as to be different from the crowd

7) The quest, ie, the thrill of the chase

Gosling, in particular, is interested in the stuff we own, surround ourselves with, and put on display, and what it might say about our personalities. There are, he says, some items that serve as “conscious identity claims”, or items we choose based on how we wish others to perceive us. This could be our music collections, posters, books, comics or the artworks we have on display.

Another function of our possessions is as “feeling regulators”. These are things that meet some emotional need – it could be an item that is tied to a strong memory, something you associate with a special person in your life, or which brings you comfort. For many, there’s a healthy dose of nostalgia tied to our collections, whether it’s remembering an earlier time in our lives, or an era we wish we had experienced.

Within those seven reasons is a subset of personality traits, identified by the choices you make when collecting and the way you organise and curate those collections. These are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. Apparently, those who file everything away neatly are likely to be on the spectrum between conscientiousness and neuroticism, while those less organised are more likely to feature under the openness and agreeableness trait. I have about 50 per cent of my collection filed but it has taken me the best part of a decade to get there – so a mixture.

Ever the iconoclast, Sigmund Freud reckoned the drive to collect came from the trauma of toilet training when we were infants, the loss of bowel control creating a yearning for things lost and our need to recover them, at least psychologically. It is a theory I find hard to accept, especially when I find a Howlin’ Wolf single in a dusty box of Engelbert Humperdinck 45s. That elicits a joy I’d never associate with the potty.

Carl Jung, though, felt the urge must be more fundamental. He postulated that any instinct to collect must stem from our previous need, in more primitive times, to gather things like nuts and berries for our survival. Good, then, that Chuck Berry and Dave Berry are such collectable recording artists.

McKinley claims there is a dark side to collecting that arises when it spills over into hoarding, the crossover delineated by whether or not it interferes with a “reasonable life” lived by the person concerned. If it does it can become pathological, with serial killers the ultimate example in that they collect people, albeit in an extreme way. The John Fowles novel, The Collector, made into a film starring Terence Stamp, explores that theme, the protagonist collecting butterflies before shifting his focus on to young women, the first of whom he kidnaps and eventually murders – essentially the plot for many a heavy metal track.

Probably the extreme illustration of this is the person who harms others in his/her passion for “collecting”. Such extreme pathology is referenced by “animal or people hoarders”. The former is the person we read about in the local paper with a headline that reads: “Local Woman Found with 100s of Filthy, Diseased, Malnourished Cats.” On the other hand, there are those collectors who collect people, as in serial killers. Movies such as The Collector, The Bone Collector and Kiss the Girls portray such persons in a context of a thrilling mystery for the entertainment of movie-goers.

But enough of the theory and back to the many-faceted practice of collecting vinyl records. None of the psychologists above explained why record-collecting, like many acquisitive pastimes, is pretty much a male preserve. Not exclusively, perhaps, but predominantly.

One theory I have is that most collectable music on vinyl is made by blokes, with the heyday being the 1960s and 70s, when male-orientated rock music ruled the roost. But that is changing with the rising collectability of female artists like Madonna and Lady Gaga.

There are women collectors; I’ve seen them in the mid-distance at record fairs. Yet, I have to report that in my 35 years of scouring racks and sifting crates, I have yet to meet one interested in the stuff that I collect – and I’d say my tastes, which don’t include Madonna, are fairly catholic.

Within that generality of being essentially male-orientated lies a myriad of reasons why people collect what they do, the causes as bewildering as the variety of music that scratches their sonic itches.

One record dealer-cum-collector I know sucked his teeth long and hard when I asked why he collected. “Better to not go there,” he said, before reluctantly proffering that it was probably a more passive version of the ancient urge to go hunting. “Back then it was to get real food to eat,” he reasoned. “But now its soul food that is needed for the mind and body, and records supply that, at least they do for me.”

Another collector, mostly of African and West Indian music, said he was almost overcome with joy recently after finding a calypso record that had proved elusive for more than 25 years. “Part of the pleasure is the treasure hunt aspect of it but a lot is also to do with the object (the record) and the tune it carries,” he said. “They stand for a time and place not all of us had the privilege to experience. For me, having the record helps to capture that.”

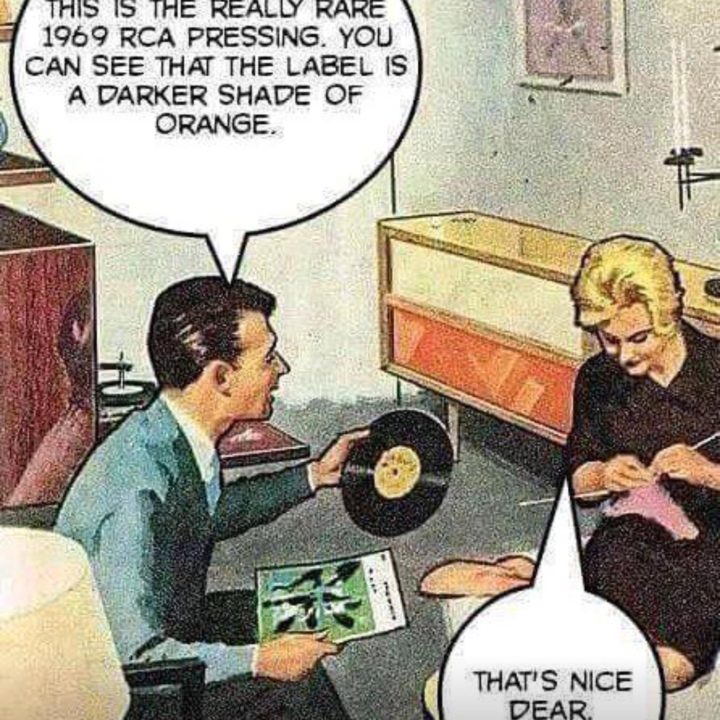

There can be a degree of one-upmanship among collectors with scarcity a highly desirable quality among certain types. There are stories of vodka parties in Moscow, where Russian oligarchs try to impress each other by playing rare records like the Ben and Still Life albums on the Vertigo label, some so valuable and in such pristine condition that gloves are worn when handling them. And yet, Mr Calypso collector would not tell me the title of his find for fear of it leaking out and arousing jealousy among the others who seek it. Far from bragging about his prize, he wanted to keep it quiet.

Piers Chalmers, another dealer who once collected and a doyen of 50s rock and roll, laments what he sees as the changing face of collecting. “Originally, it was about the music and it was all very social,” he said. “In the 1970s, a whole load of us would meet up on a Friday at the Marquis of Granby in Covent Garden and bring our latest rockabilly finds with us. Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page would be there hoping to buy or swap any spares we might have. But all people talk about now is what a record is worth, not about the music. Investment value appears to have trumped all other considerations such as: is it any good?”

Others collect for the same reason that some follow football teams: to be tribal. They want to show their allegiance to a certain band or pop star and to assume a commonality with like-minded souls. Their motivation? That feeling of belonging, with the safety and empowerment it confers.

When friends ask what goes on at record fairs and what most people are after, I tell them, flippantly, Queen picture discs and stuff by David Bowie, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. And broadly that is true. The most popular artists are the pillars of record-collecting and while many will concentrate on just one of them, they do so to the point of obsession, seeking out everything that has ever been released by their chosen ones, irrespective of year or country.

Actually, most who collect tend to specialise, their area of interest narrowed either by format (LP, 45 or EP), artist or genre. Expense is one reason. Some records can still be picked up for a few quid but many, like, say, first pressings of jazz records on the Blue Note label, especially those released from the Lexington Avenue address in New York, can fetch £1,000 or more.

Storage can also be a factor. LPs, which are the mainstay of most collectors, are both large (12in x 12in) and heavy (anything from 140 to 180 grams). Unless you own a big, dry shed, garage or warehouse, you may have to settle for a stash in the hundreds rather than the thousands. It is not unknown for some to get rid of chairs, sofas and tables in order to house their collection at home.

Some stick to genres like French yé-yé, soul, prog, R’n’B, freakbeat, roots reggae, ska, funk or death metal, to name but a few. For newcomers it can be a daunting prospect. Few, though, are judged as harshly as the hapless record shop customer in High Fidelity, Nick Hornby’s astutely observed novel about music and life. There, an enquiry about Stevie Wonder’s I Just Called to Say I Love You is met with a scorn I’ve yet to encounter. Even so, it helps to know your nu-folk from your NWOBHM (new wave of British heavy metal, as I’m sure you knew).

The bullseye for me is something rare and dynamic, which would discount most Top 40 hits since they sold well. I’m after a song, or piece of music within it, that sparks a hitherto unfelt emotion or feeling of pleasure. Obscure is good but obscure and good is even better.

It is a quest, a voyage of discovery rather than a nostalgia kick. But I know what I like. There are some records, even enticingly obscure ones, that I would draw the line at owning, such as the Gordon record on Vertigo or the Spring LP on RCA Neon. Rare records are often rare because they sold poorly and there is a reason for that – they are crap.

For me, the life stories of a band or artist, their drug-taking, mythology and so on, are of less interest than the production and engineering of what I am hearing. Unless the recording is live, there are many ways to mix a record but why was the chosen way chosen? The music business is littered with bands switching producers in the hope of a better sound or feel to their record.

I defy anyone not to marvel at the exquisite tone – on vinyl – of Peter Green’s guitar on the B-side of a John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers single from 1967. The track, entitled Out of Reach, is a slow, lamenting blues driven by a brooding bassline from John McVie. But it is the reverb added to Green’s imploring guitar by an in-house producer at Decca that gives the song its ache and anguish. On the original 45 it is utterly spine-tingling.

I seek and fetishise original first-pressings. These can cover a wide spread in the case of big-selling bands like the Beatles or Rolling Stones. The closer the pressing is to the first stamper, which is the metal plate produced from the master disc that stamps an imprint of the record into the vinyl puck on the record presses, the better its sonics – at least that is the theory. To determine the pressing, you have to become fluent in reading matrixes and knowing the detail of sleeve and label design.

There were at least five variations of Led Zeppelin’s fourth LP (the one with no title other than four symbols and featuring the ubiquitous Stairway to Heaven) even before the second issue came out on the green and orange Atlantic label. For those on the original red and plum label, one has an inverted feather (one of the four symbols), one has a sticker on the label covering up an erroneous Peter Grant production credit and one doesn’t. Another has Led Zeppelin printed on the lower half of the label while the other has it on the top half. I don’t know who at Atlantic consented to these subtle redesigns (the story goes they were driven by Jimmy Page), but for completists they have been expensive: none of these variations goes for less than £100.

Or take Rubber Soul, released by the Beatles in 1965. The yellow and black Parlophone first pressing in mono, with the XEX 579-1 and 580-1 matrices signifying the legendary “loud cut” in which the vocal tracks are boosted to sound more raw (a feature the record company didn’t like and which led to that particular release being pulled and replaced by a “softer” version), creates an instant link to those times. I don’t go the full 60s retro and play such records on a Garrard SP25 deck with Decca cartridge, valve amplifier and Quad ESL speakers, but I know people who do.

A fellow collector, Jonathan Crawford, concurs with this special nexus to source, saying that every time he puts on a first press of Miles Davis on the Prestige label, with their thick squared-off edges, it takes him back to 1950s New York, or at least his idea of it given he is a 65-year-old who missed the city’s jazz heyday. It’s a connection that seems to add to the experience of listening to records, hence the obsession with finding copies from the era in which they were pressed.

Crawford also speaks of the competitive element and the “ineffable sense of loss” collectors feel when the crate digger in front of them, one who may have been even more thorough in sifting through the boxes of dross, plucks the very record they, too, were after. “I’ve seen fights, not fists, but certainly the odd tug-of-war,” he says.

Reissues, apart from being inferior in both sound and feel to an original – often the vinyl and card for the cover are thinner for a start – simply lack that cachet. Indeed, I recall finding a 1958 Sun Ra original of Jazz in Silhouette in a Leeds record shop. The vinyl was thick and heavy but it was expensive, so I left it there. I regret that every day; I’ve never seen another and probably never will.

Yet others just want the song and are happy to have it on reissue vinyl, CD, cassette or digital file. Poor saps, they are missing the visceral thrill that comes from possessing the genuine artefact.

Boarding school is where I began to obsess about music, though I enjoyed it and was curious about it much earlier in Nairobi, where I was born and brought up. The move into second-hand records happened in the late 1980s after a trip to New York, to play cricket of all things. Seduced by a huge billboard that declared: “Tower Records – World’s largest record store” I went along to explore its five or six storeys only to find a small, unloved section of about 1,000 vinyl records tucked away on the top floor. Compact discs ruled.

The distinct demotion of vinyl at this supposed emporium spurred me into looking elsewhere and it was on that trip that I encountered my first second-hand record shop: House of Oldies in Greenwich Village. It was revelatory and a whole new and fascinating world, from Melbourne to Mumbai, opened up for me.

With global travel part of my life as both cricketer and, latterly, cricket journalist, the pre-internet age was a boom time. Not only did record-sellers in places like Christchurch, New Zealand not know the true value of some records, but rival collectors had yet to visit these places, which they tended not to do given the expense of travelling that far. These days the price of records and their availability is all possible at the click of a button, which has removed the advantage someone like me used to have.

To add to the excitement, even now, detective work is sometimes required. I once tracked down a record manufacturer to a cloth factory in Nairobi. It was worth it. The factory, in a distinctly dodgy part of town, had housed both a studio and a small pressing plant in the 1950s and 60s for a label called CMS. That all changed in the 70s when it decided to mill cotton to make cloth. Yet, tucked away in its dark recesses were hundreds of boxes of white label singles, dusty but otherwise in mint condition, which the owner let me have for a song.

Then there was the legendary back room at Rhyner’s Record Shop in downtown Port of Spain, another place you wouldn’t want to be wandering round after dark. That room, which had a hole in the tin roof through which rain and rats came, yielded gems like the legendary Jazz Jamaica album by the nascent Skatalites band, as well as rare records like Northeast, a prog album on the Regal Zonophone label you would not expect to see in Trinidad. There were a dozen copies of that, twice as many as I have seen in all the record fairs I have ever attended.

It has all added up and what began just over half a century ago, with a few choice records bought for me by my parents, has grown over the intervening years into a solo enthusiasm of around 5,000 records, of various hues and sizes – too many to play every one again in my lifetime.

The compulsion to keep adding and never subtracting is one that afflicts most record collectors. When I asked a dealer about some of his clients he told me of one who willingly pared down his life in order to keep any spare cash to feed his vinyl habit. Another dealer, who owns a shop in south London, talked of the personal hygiene issues of many who frequent his premises. “They’d clearly rather spend their money on records than soap or deodorant,” he noted.

The search for used records has shifted from the shop to online, though there are still dealers, like Pete Flanagan, who operate in a limbo land between the two, relying on extensive contacts and record fairs.

I have never purchased a record on eBay or Discogs, the two main online sources. Seeking out vinyl from the comfort of one’s armchair is not for me. For one thing I like to see used records in all their glory, or not, and perhaps even to play them, to ensure any prospective purchases can hold their own in an already crowded collection. I know there are rare records on my “wants” list that I will probably never find or own. But I’ll go on looking.

This article by Derek Pringle was first published by Tortoise in April 2020. You can find out about a new kind of slow news at www.tortoisemedia.com